The problems facing advanced, post-industrial society in 2015 are pretty gob-smacking, yet the average Western adult seems bereft of reasons to leave the sofa and the younger generation find themselves shafted by a consensus that leaves them 7% poorer than they were in 2007. Whilst we continue to venerate extreme youth, we blithely block opportunity for all but the most privileged. The world sinks like a mammoth in a tar pit of economic, social and creative malaise. Nowhere is this more true than in the United Kingdom and the United States of ‘merica. Whilst both economies are, on the face of it, well into recovery, this is coupled with Victorian levels of income inequality and a suffocating sense of cultural ‘meh’.

Today’s skateboarders are different: we’re more motivated than ever to get up and reshape our little worlds, albeit on a usually local scale (with the exception of those saint-like men and women who’ve jetted off to Afghanistan or Palestine with quivers of skateboards and big ideas). A flurry of DIY skate-spots, independent start-ups, giant-slaying community activism, film, art and all sorts of other weird things (including ramps on train tracks and bowls in trees) combining wheelbarrows full of ‘crete with end-of-times frontier survivalism. This makes it pretty hard for an active skateboarder to be jaded even whilst the wider world is kind of awful.

In the midst of all this energy, British skateboarding seems to have rediscovered its love of America, and Americans are returning the favour. Or so you’d conclude from the internet echo chamber of obsessives and taste-makers. Kids in small-town skate parks in either country appear largely unaffected by the cultural shifts that excite the 1%, as was ever the case.

Up until some point in the early to mid-2000s, all of skateboarding looked to a corner of Southern California (and occasionally northern California and cities along the Eastern Seaboard if you were more esoterically inclined). Skateboarding was small, full of new and exciting brands – almost all of them American. If you were growing up in Britain, the Americans had the spots, the skills, and the vision of how skateboarding should look like. The mark of a good European brand was to successfully appear American. Sure, many Brits and Europeans made it, both on their planks and to high places in the industry – Pierre André Senizergues, Jeremy Fox, Penny, Shipman, Rowley, etc. – but the unwritten rule was that to really do it in skateboarding, you had to do it in the United States.

But then a succession of events shifted the axis for UK skaters. British skating established an identity and pride through Sidewalk magazine and Blueprint (with which Dan Magee suavely re-imagined East Coast US brands with references to tea, rain and Morrissey lyrics). The European scene exploded and Barca replaced SF as the destination of choice, enabling Puzzle then Kingpin to legitimately and fruitfully document skateboarding without having to look across the Atlantic. In comparison, a large share of American skating pumped up on elitist handrail athletics, logo boards and identikit epic videos, got pretty dull. Sure, there were shining exceptions of consistent quality, 20 years deep. But like your favourite bands in adolescence, attention craves new shit. Somewhere between the dying of the embers of 2000’s Photosynthesis and the arrival of Cliché’s Bon Appetit (2004) and Blueprint’s Lost & Found (2005), I realised I’d fallen out of skate-love with America. I read Sidewalk, Document and Kingpin and rarely looked at Thrasher or Transworld. I looked to British or European skaters for inspiration, jumping from Colin Kennedy to Jan Kliewer and JJ Rousseau. Only as Youtube became all pervasive in the late 2000s, did I start regularly looking back at the old US favourites.

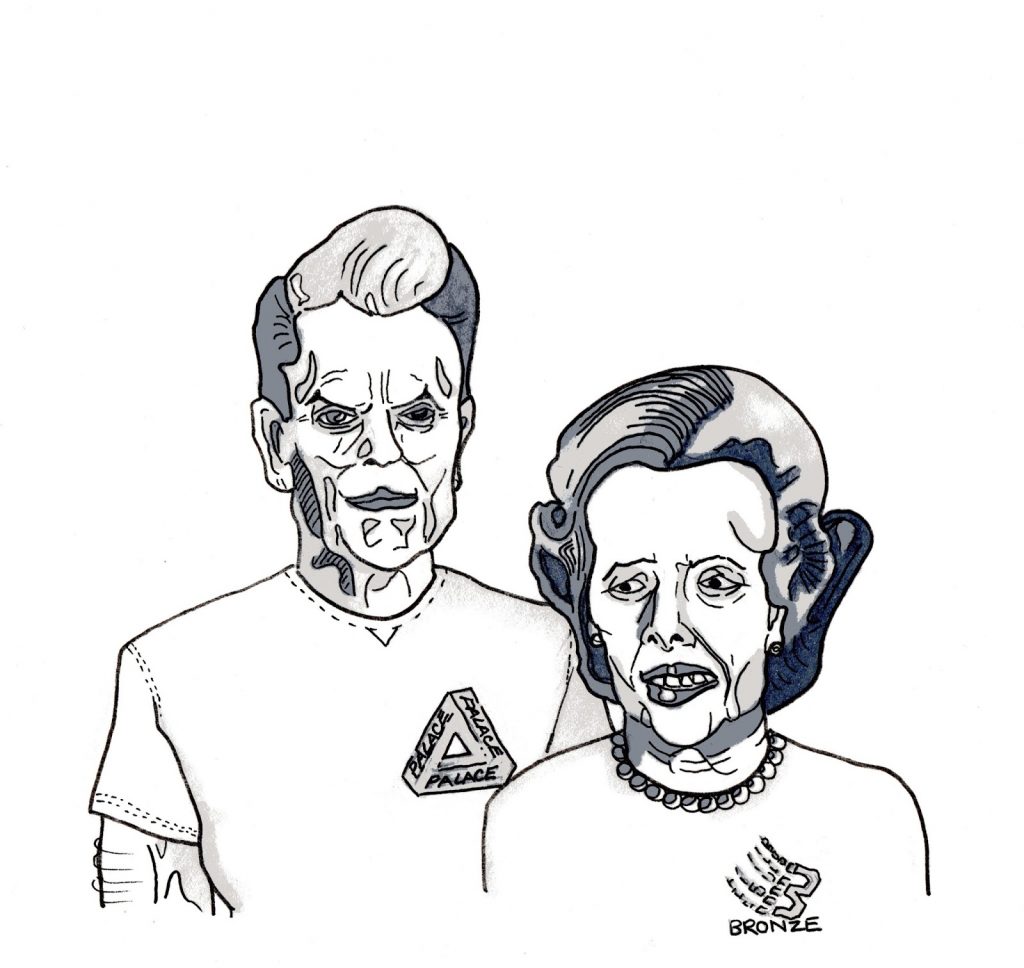

In the last few years this has changed. The first indie brands to make a big impact may have been European, notably Palace, Polar and Magenta, but a call-and-response momentum has pinged back and forth across the Atlantic with like-minds in the US, such as Hopps, the Northern Co, Welcome, Bronze and Politic offering a view of skating in contrast to Street League and post-colonial filming trips to deserted East Asian plazas. That’s before we get to the indie film-makers from the US delighting the cool kids in Britain and dramatically tipping the US/UK footage viewing scale that’s been weighed in the other direction for the best part of a decade.

And now taste makers in the US and UK are fluttering their eyelashes at one another, with skate geeks and keyboard warriors from either skate scene keen to consume an idealised version of the other. When you read US coverage around the recent Palace-Bronze collaboration or excitement over the inclusion of American and Canadian riders on the Palace roster, it’s illuminating how this reflects US assumptions about UK skateboarding and Britain more widely. Blissed-out house and crackly VHS become short-hand for multicultural, belligerent and swaggering London. This is a million miles away from the lived experience of Luton or Grantham, or Bournemouth and Chipping Norton. Down-at-heel dreariness or leafy, sleepy Little England are far from the idealised symbolism of ultra-modern Britain that Americans seem keen on via Palace (recently confirmed by none other than the Gonz as just as big a deal in the States as they are in the UK).

The special relationship between skateboarding in the two countries is far from equal because it’s not based on a comparable level of familiarity. Consumers in the UK are well aware of the dross produced by the bottom end of the American skate industry, the straight-to-mall brands that fill Transworld’s monthly advert broom-cupboard. We choose to consume the very best, or the most interesting, of literally thousands of US companies. Insular Middle America is there in the stuff we could buy into, but we choose not to – preferring our own set of idealised characteristics invariably connected to modern, liberal and outward-looking urban America.

Skate nerds in the US don’t have to make that choice. Only the best UK and Euro stuff makes it in the other direction across the pond. In the early 2000s, I suspect most Americans who knew about and were stoked on Blueprint – and took it as short-hand for an earlier ideal of London, understated and urbane – were totally ignorant of Reaction: the skate equivalent of a British commuter town, all chain pubs and indoor shopping centres, pissing away an amazing team with lack-lustre graphics and lazy branding. The ‘rough spots/stylish skaters/cool brands’ formula with which New York’s Quartersnacks describe UK skating is flattering n’all, but any British skater can think of a dozen towns where MTV emo and boneless finger flips are alive and well across the local skate park inhabitants.

This dichotomy is also true for much of grass-roots American skaters, with Jenkem’s illuminating interviews with regular kids showing that the cool US, UK and Euro indie brands aren’t on the radar for those minors who account for the largest share of US domestic skate sales. By choosing which internet echo chamber we participate it (i.e. not any of this stuff), we blare at each other about exclusively good shit that is unrecognisable from the much bigger world of Monster-fitted caps and 1,000s of clips of cringeworthy nonsense. This is of course a micro-example of the bafflement liberals in the US express when UKIP get 10% of the vote in the last British election, or in the UK when we hear of each US high-school shooting, and subsequent noisy and counter-intuitive renewal of the ‘right to bear arms’ argument. How can a country that brings us amazing music and film also voice significant opposition to equal marriage rights? The majority are numbskulls on both sides of the pond.

A final question is ‘why now’? With Palace going from strength to strength, and more old and new UK companies, filmers and crews than ever, and with Europe an equally powerful draw (not least the pulse emanating from the small Swedish city of Malmö), why on earth should America have gotten cool again? It’s a nightmare to actually skate there, and US sources still pump out a corny, commercialised take on skateboarding like it’s going out of fashion (when will it go out of fashion…?). Obviously, America has always had rad stuff going on – and the internet seems to speed up the cycle of one thing becoming hot shit in the eyes of another. The answer likely goes back to the rise of indie brands. If we got bored of the mainstream as established by the US, it wasn’t because we got bored of American stuff per se. We’d just seen so much lookalike product churned out by the same generation of people who held/still hold the keys to the kingdom. Now the doors have been flung open, and Americans have proven every bit as able to produce exciting, small-scale stuff as a bunch of bros from Bordeaux, Malmö, Tokyo or London, reviving the temporarily dormant interest in things American – especially if it evokes grand old, grimy East Coast cities, or hilly, windy West Coast ones. As was ever thus: although the average kid still chooses the energy drink cap or logo board here as well as there.

For this and other weird rambling: http://morboknows.blogspot.co.uk/